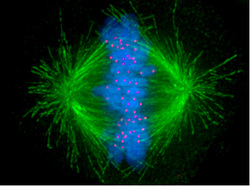

Cell division is, like planetary motion, a beautiful balletic phenomenon. But understanding it, which is still at a rudimentary stage, currently involves arguments such as this:

“Human centromere protein A (CENP-A) chromatin is constitutively associated with a complex of 16 centromere proteins (2, 3). Among these 16 proteins, only CENP-C has been identified in all model organisms (4). CENP-C recognizes the carboxyl tail of CENP-A in the centromeric nucleosome (5, 6). Human CENP-C consists of four functional regions (fig. S1A). The N-terminal region interacts with the Mis12 complex (7). The central region and the CENP-C motif are required for targeting CENP-C to the centromere (5, 8–11). The central region directly binds to the CENP-A nucleosome, whereas the targeting mechanism for the CENP-C motif is unknown. The C-terminal region is responsible for CENP-C dimerization (12).”

Sadly, it seems unlikely that biology will ever resolve from such complexity into a simple Newtonian system. The last time it looked as if it might was the famous moment 60 years ago when Watson and Crick published their DNA structure with its beautifully provocative conclusion:

"It has not escaped our notice that the specific pairing we have postulated immediately suggests a possible copying mechanism for the genetic material".

That “possible copying mechanism” was more attractive when notional; now, it seems a complete mess.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed