|

A foggy dew of a morning reveals a garden festooned with triangulated nets of spider webs. It looks as if an arachnid Buckminster Fuller or Frei Otto has been at work. Magical!

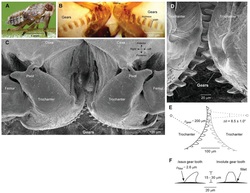

It is often idly said that “Nature never invented the wheel”. It’s not true – every cell contains tiny rotating dynamos powered by ATP. But gears? That must be impossible. But in a recent issue of Science, two British researchers (Cambridge and Br pistol) have discovered a perfectly meshed gear system in the jumping mechanism of the flightless planthopper insect Issus coleoptratus. The teeth project by about 15-30 μm. Strangely enough, having evolved this exquisite mechanism, the planthopper discards it in the final moult – the adult lacks the gears although it can still jump. The authors speculate that the gears would be a liability in the adult because should the teeth break there is no insect gear repair shop to which they can hop to get a replacement. Nature’s regenerative, self-healing capacities are legendary but they don’t extend to gears. Science 13 September, 2013, pp. 1254-56 Adverts for the “new” TSB reveal the brazen shamelessness of the financial sector. They tell the story of the Reverend Henry Duncan who in 1810 founded “a bank for hard working local people”. The new bank has been created by the Europe Union forcing the giant Lloyds to divest itself of a proportion of its business. Clients have been arbitrarily assigned to the new bank, after which they can choose to stay or to take their money elsewhere. The gruesome machinations of international financial institutions and EU bureaucrats could not have less to do with the establishment of an ethical people’s bank back in 1810. But that doesn’t stop them spinning this preposterous yarn.

“You won’t find us doing things like investment banking, international funding or big corporate finance”, they say. But it is exactly those things that led to the state rescue of HBOS, their subsequent takeover by Lloyds and this latest demerger. Two recent studies published in Nature and Cell, respectively, reveal how fast we are learning the deepest secrets of the perpetuation of life. In 2006 it was discovered for the first time how to reprogram adult cells, skin cells for example, into stem cells that could develop into any other tissue. Only four genetic transcription factors were needed to produce this transformation. In July this year it was shown that seven quite simple chemicals could substitute for the transcription factors.

The stem cells produced are known as pluripotent, that is, they can be induced to develop into a variety of different organs. The next stage is to make pluripotent cells totipotent – ie to create sperm and eggs. This is what the Nature paper reports. Both the original breakthrough and the new study come from Japan. Mitinori Saitou’s team at Kyoto University has created mouse sperm and egg cells from pluripotent stem cells that have gone on to produce viable fertile mice. What is most striking about this is that a few factors – four in the case of reprogramming adult specialised cells and three in the case of creating sex cells, can throw the master switches for the enormous cascade of development that results in an adult. At the other end of the scale, a recent evolutionary study of the genes that control the development of mammalian limbs has shown that compared to mice and macaques 3000 human enhancers and 2000 promoters are active in limb development. These are not completely different genes to those of mice and macaques but genes of common origin that show changes in the human line selected during evolution. Which means that the early big decisions, ie male or female, can be controlled by three or four genes but the fine tuning that makes the human form subtly different to that of other mammals requires endless tinkering at many stages of development. Once you know this it makes sense. Naively we might think that the factors that set in train the fertilisation of an egg and subsequent growth must be the base of the pyramid. But they are the tip. This why the embryos of many creatures, not just mammals, look virtually identical. All the complex tweaking occurs downstream. Nature, 8 August, 2013, pp. 158-9 and Cell, 2013, 154, pp. 185-196. Nature, 12 September, 2013, pp. 222-226.  The latest Science to land on my desk has a paper on the migration of whooping cranes in America. The cranes are endangered and there is a program to breed them in captivity. An obstacle that had to be overcome was the birds’ annual migration from the breeding site in Wisconsin to Florida. It seems that they rely very heavily on learning from experienced birds so a colony of naive birds facing their first migration has problem. The answer is ingenious and beautiful. A human-powered microlite guides them on their first migration and they are able to find their way back. In subsequent years their navigation improves as the learning process consolidates. In San Diego, earlier this year, I watched pelicans flying home in their shifting V formations. They gave out had aura of control, power and even wisdom. To see that the cranes are able to trust the human navigator for the first trip is very moving. Science, 30 August 2013, pp. 999-1002. No, not the painting: the 1968 album by the New Jazz Orchestra. It has been one of my favourite albums for 45 years yet it is still not available in digital format. It is British jazz, of course, which might explain the neglect, but there is nothing remotely parochial about it. It involves the best British jazz composers ( Michael Garrick, Mike Taylor, Mike Gibbs, Neil Ardley) and the best musicians: Henry Lowther, Ian Carr, Dave Gelly, Frank Ricotti, Barbara Thompson, Jon Hiseman , Jack Bruce et. A couple of tracks are by Coltrane (Naima) and Miles Davis (Nardis).

Neil Ardley is the Director and Arranger of the album and the work is clearly in the line of Gil Evans’ work with Miles Davis. But the gorgeous textures, clear melodies, wonderful skirling brass section, and the jazz-rock underpinning of Hiseman and Bruce lift it clear of any taint of derivativeness. Searching for a digital version I came across a live recording of some of the tracks on Camden ’70, a Live album. This is OK but lacks some of the finesse of the studio recording. Tony Reeves is on bass rather than Jack Bruce, the rhythm section sounds more like the rock band Colosseum than the NJO at times, and some of the tempi are too fast. There’s always something to learn. In my fruitless search for the digital Dejeuner I discovered Neil Ardley’s biography for the first time. He was 10 years older than me but, like me, studied chemistry at Bristol University. He didn’t make his living from jazz but from writing popular science books. He wrote 101 books in this genre. I too write popular science books and play a bit of jazz guitar. So Ardley is a hero I hardly recognised until now.  A Brimstone Moth (Opisthograptis luteolata) blew in on the balmy breeze last night. Sorry the poor focus pic doesn't do justice. Must get a moth trap. Richard Williams is Chief Sports Writer for the Guardian but he made his name as the best popular music journalist in Britain. He was then for a time Head of A&R at Island Records. He writes books on music now, not articles, but he does blog on music in The Blue Moment. Williams is unusual amongst music writers. As he says, he’s interest in the mechanics of music: “The way that the backbeat and bass line works, rather than something else. That's how I listen to music. I listen to the notes.” Highly recommended.

|

AuthorI'm a writer whose interests include the biological revolution happening now, the relationship between art and science, jazz, and the state of the planet Archives

March 2016

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed