Lucretius: The Secret Life of the

Nature of Things

Science and poetry have been the twin poles of my life: I studied chemistry, spent sixteen years editing a poetry magazine, and am now mostly a science writer. So at some stage I was bound to be brought face to face with the Roman poet Lucretius (c.99-55 BCE), whose long poem De rerum natura (The Nature of Things) is one of the great meeting points of science and literature.

I can trace my first encounter back to my university physical chemistry textbook, in which Lucretius is quoted in the chapter on gases and how their temperature and pressure depend entirely on the agitated rapid motion of the molecules that compose them. This wasn’t mere classical ornamentation because Lucretius expounded – with many ingenious and elegant arguments, which I take to be mostly his own – the atomic theory of the early Greek philosophers Democritus and Leucippus, as later developed into a full-blown worldview and moral philosophy by Epicurus. The Greek atomic theory was the only one of many pre-scientific speculative theories that would come to be vindicated by science, and passages in Lucretius directly inspired the architects of the theory of gases: Robert Boyle in the 17th century and James Clerk Maxwell in the 19th century. Of what other 2000-year-old work on nature could it be said, as did the physicist E. N. da Costa Andrade, as recently as 1928: “Here we find the kinetic theory of matter described in outline, with illustrations which would not be inept in a present-day treatise”?

I was intrigued but in those days a chemistry degree course didn’t encourage art-science meanders. I finally bought the book in 1971 at the age of 24, in the lucid and accessible Penguin Classics prose translation by Robert Latham. The Nature of Things has come along with me since then. I’ve read it many times and in other translations and by now it is obvious that it is my book of a lifetime.

Asked to name five supreme classical authors, most people would not reach for the name Lucretius but he deserves such a place because he is the secret source of modernity, a one-man Enlightenment, 1800 years ahead of the letter. Homer, Plato, Aristotle, Virgil, and Horace are preeminent in their context but they are not moderns in the way that Lucretius is: they didn’t make dazzling speculations across a whole range of knowledge – physics, human history, earth science, sexual psychology – that have turned out to be prescient, all couched in pithy wisdom and urbane verse. Lucretius belongs on the masthead of our culture; he was a pioneer in trails later blazed by Leonardo, Galileo, Newton, Locke, Voltaire, Darwin, Einstein and Freud.

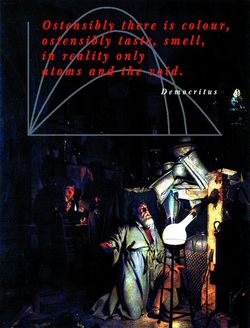

The Nature of Things is an attempt, by a Roman contemporary of Julius Caesar, one schooled in the best of Greek philosophy, to explain life, the universe and everything. The poem’s descriptions of nature and human society celebrate all that is benign and civilised whilst excoriating cruelty and the dark fears that have beset humankind for its entire existence. Lucretius gives a highly plausible account of humanity’s rise from an animal existence, through the violent era we now call the Bronze Age, to the enlightenment provided by Greece, Lucretius’ touchstone. At the centre of the poem is the atomic theory of Democritus, Leucippus and Epicurus. But Lucretius was not merely paraphrasing the theories of others: his arguments that matter consists of tiny particles in a limited number of types are ingenious, brilliantly expressed, and many have stood the test of time.

Who was Lucretius? No reliable knowledge of the man has come down to us: he is more mysterious than Shakespeare, with whom he has been compared by the philosopher George Santayana:

Poetic dominion over things as they are is seen best on Shakespeare for the ways of men, and in Lucretius for the ways of nature.

If clues exist, the most likely place is a villa in the other town buried by Vesuvius in 79 CE: Herculaneum. Pompeii and Herculaneum are replete with treasures, as the recent exhibition at the British Museum demonstrated once again. But despite over 250 years of excavation, these sites still harbour secrets, none more tantalising than the library of one of the villas in Herculaneum, the Villa dei Papiri, as it is now known.

The Nature of Things is our principal source for the Greek philosophy known as Epicureanism, after its founder Epicurus, who used the physical theory of atomism conceived by Democritus and Leucippus to develop a materialist philosophy that shunned supernatural belief, disavowed terrors beyond the grave, and prescribed a calm life, seeking pleasure within reasonable boundaries.

Although the words are Voltaire’s, Epicurus was the originator of the principle “We must cultivate our garden”. The Bay of Naples was originally a Greek settlement and in Lucretius’ day was home to a colony of Greek Epicureans who sought to recreate an Epicurean garden and to live the contemplative life recommended by the master. Lucretius’ connection with this community is a matter of speculation.

The original owner of the Villa dei Papiri has been tentatively identified as Lucius Calpurnius Piso Caesonius (fl. 58 BCE), a rich Roman senator whose daughter Calpurnia married Julius Caesar. The library of the Villa dei Papiri, comprising many papyrus scrolls, is the only extant library coming down to us from classical times.

The papyrus scroll was the Roman book: handy to store but cumbersome to read. Herculaneum was closer to Vesuvius than Pompeii and the flow of gases and rock was hotter (up to 400oC). Most of the scrolls were completely carbonized. But hi-tech instruments for probing archaeological remains have reached a peak of forensic excellence. There are now ways of recovering text even from totally carbonized scrolls.

The Herculaneum scrolls clearly constituted the library of an Epicurean philosopher and most of the works are by a single hand: one Philodemus (100-c.40-35 BCE). The eruption of Vesuvius was, of course, much later than this – 79 CE – but the mass of material by this one author makes it likely that the library had been preserved intact from the former era. That it is the working library of a fairly humdrum writer is disappointing but the work of decoding the scrolls will go on for a long time. In 1989 one of them was adjudged to contain fragments from The Nature of Things. Given the subject matter of the library, it would be surprising if Lucretius were not represented but the fragments deciphered so far are a very small fraction of the whole. Herculaneum has never been fully excavated and it is very likely that there are further clues to Lucretius in vaults still buried under volcanic debris.

With the fall of the Roman Empire, Lucretius was lost from view for 1000 years. The Nature of Things re-entered the world thanks to the manuscript hunter Poggio Bracciolini who, in a story told in Steven Greenblatt’s The Swerve (2011), discovered a copy of the poem in 1417 in a German monastery. From now on, the Lucretian poem was potentially available but dissemination was initially slow until the first printed edition in 1473.

READ MORE

Nature of Things

Science and poetry have been the twin poles of my life: I studied chemistry, spent sixteen years editing a poetry magazine, and am now mostly a science writer. So at some stage I was bound to be brought face to face with the Roman poet Lucretius (c.99-55 BCE), whose long poem De rerum natura (The Nature of Things) is one of the great meeting points of science and literature.

I can trace my first encounter back to my university physical chemistry textbook, in which Lucretius is quoted in the chapter on gases and how their temperature and pressure depend entirely on the agitated rapid motion of the molecules that compose them. This wasn’t mere classical ornamentation because Lucretius expounded – with many ingenious and elegant arguments, which I take to be mostly his own – the atomic theory of the early Greek philosophers Democritus and Leucippus, as later developed into a full-blown worldview and moral philosophy by Epicurus. The Greek atomic theory was the only one of many pre-scientific speculative theories that would come to be vindicated by science, and passages in Lucretius directly inspired the architects of the theory of gases: Robert Boyle in the 17th century and James Clerk Maxwell in the 19th century. Of what other 2000-year-old work on nature could it be said, as did the physicist E. N. da Costa Andrade, as recently as 1928: “Here we find the kinetic theory of matter described in outline, with illustrations which would not be inept in a present-day treatise”?

I was intrigued but in those days a chemistry degree course didn’t encourage art-science meanders. I finally bought the book in 1971 at the age of 24, in the lucid and accessible Penguin Classics prose translation by Robert Latham. The Nature of Things has come along with me since then. I’ve read it many times and in other translations and by now it is obvious that it is my book of a lifetime.

Asked to name five supreme classical authors, most people would not reach for the name Lucretius but he deserves such a place because he is the secret source of modernity, a one-man Enlightenment, 1800 years ahead of the letter. Homer, Plato, Aristotle, Virgil, and Horace are preeminent in their context but they are not moderns in the way that Lucretius is: they didn’t make dazzling speculations across a whole range of knowledge – physics, human history, earth science, sexual psychology – that have turned out to be prescient, all couched in pithy wisdom and urbane verse. Lucretius belongs on the masthead of our culture; he was a pioneer in trails later blazed by Leonardo, Galileo, Newton, Locke, Voltaire, Darwin, Einstein and Freud.

The Nature of Things is an attempt, by a Roman contemporary of Julius Caesar, one schooled in the best of Greek philosophy, to explain life, the universe and everything. The poem’s descriptions of nature and human society celebrate all that is benign and civilised whilst excoriating cruelty and the dark fears that have beset humankind for its entire existence. Lucretius gives a highly plausible account of humanity’s rise from an animal existence, through the violent era we now call the Bronze Age, to the enlightenment provided by Greece, Lucretius’ touchstone. At the centre of the poem is the atomic theory of Democritus, Leucippus and Epicurus. But Lucretius was not merely paraphrasing the theories of others: his arguments that matter consists of tiny particles in a limited number of types are ingenious, brilliantly expressed, and many have stood the test of time.

Who was Lucretius? No reliable knowledge of the man has come down to us: he is more mysterious than Shakespeare, with whom he has been compared by the philosopher George Santayana:

Poetic dominion over things as they are is seen best on Shakespeare for the ways of men, and in Lucretius for the ways of nature.

If clues exist, the most likely place is a villa in the other town buried by Vesuvius in 79 CE: Herculaneum. Pompeii and Herculaneum are replete with treasures, as the recent exhibition at the British Museum demonstrated once again. But despite over 250 years of excavation, these sites still harbour secrets, none more tantalising than the library of one of the villas in Herculaneum, the Villa dei Papiri, as it is now known.

The Nature of Things is our principal source for the Greek philosophy known as Epicureanism, after its founder Epicurus, who used the physical theory of atomism conceived by Democritus and Leucippus to develop a materialist philosophy that shunned supernatural belief, disavowed terrors beyond the grave, and prescribed a calm life, seeking pleasure within reasonable boundaries.

Although the words are Voltaire’s, Epicurus was the originator of the principle “We must cultivate our garden”. The Bay of Naples was originally a Greek settlement and in Lucretius’ day was home to a colony of Greek Epicureans who sought to recreate an Epicurean garden and to live the contemplative life recommended by the master. Lucretius’ connection with this community is a matter of speculation.

The original owner of the Villa dei Papiri has been tentatively identified as Lucius Calpurnius Piso Caesonius (fl. 58 BCE), a rich Roman senator whose daughter Calpurnia married Julius Caesar. The library of the Villa dei Papiri, comprising many papyrus scrolls, is the only extant library coming down to us from classical times.

The papyrus scroll was the Roman book: handy to store but cumbersome to read. Herculaneum was closer to Vesuvius than Pompeii and the flow of gases and rock was hotter (up to 400oC). Most of the scrolls were completely carbonized. But hi-tech instruments for probing archaeological remains have reached a peak of forensic excellence. There are now ways of recovering text even from totally carbonized scrolls.

The Herculaneum scrolls clearly constituted the library of an Epicurean philosopher and most of the works are by a single hand: one Philodemus (100-c.40-35 BCE). The eruption of Vesuvius was, of course, much later than this – 79 CE – but the mass of material by this one author makes it likely that the library had been preserved intact from the former era. That it is the working library of a fairly humdrum writer is disappointing but the work of decoding the scrolls will go on for a long time. In 1989 one of them was adjudged to contain fragments from The Nature of Things. Given the subject matter of the library, it would be surprising if Lucretius were not represented but the fragments deciphered so far are a very small fraction of the whole. Herculaneum has never been fully excavated and it is very likely that there are further clues to Lucretius in vaults still buried under volcanic debris.

With the fall of the Roman Empire, Lucretius was lost from view for 1000 years. The Nature of Things re-entered the world thanks to the manuscript hunter Poggio Bracciolini who, in a story told in Steven Greenblatt’s The Swerve (2011), discovered a copy of the poem in 1417 in a German monastery. From now on, the Lucretian poem was potentially available but dissemination was initially slow until the first printed edition in 1473.

READ MORE