|

Dazzle painting of ships hasn't been much used since World War I (see Dazzled and Deceived) so it was a surprise to see a rather beautiful version on a Chinese missile ship test-firing its hardware recently.

_ The mystery of form is one of nature’s deepest secrets. It has attracted some of the greatest minds, both scientific and artistic, from Aristotle through Leonardo and Durer in the Renaissance, to Alan Turing in the 20th century.

Form and pattern are the natural meeting place of art and science so why is it that we don’t know more about this magic land where the lion of science lies down with the lamb of art? The reason is the strange status of form in science – its relative neglect. Darwin wrote of ‘Endless forms most beautiful’. But he knew nothing of the processes that created these forms: natural selection is a sieve of possible forms, not the generating mechanism itself. It is only in the last 30 years that biological pattern-making has come of age. But, as with every subject, there is a pre-history. There are unsung pioneers. The undisputed prophet of biological form is D’Arcy Wentworth Thompson (1860-1948). Thompson was a great Victorian, Scottish polymath. I say Victorian although he died in 1948. But everything about Thompson was redolent of 19th century genius. He was a mathematician and a classicist as well as a biologist. He was regarded as being outside the biological mainstream until the new science of biological form, evo devo, took off in the 1980s. Thompson didn’t like the indirectness of Darwinian natural selection. He thought that physical forces acted directly on living things to shape them. He showed how soapy foams template the intricate geometrical forms of the marine creatures, radiolarians. There is a whole geometry that connects soap bubbles, the radiolarians, bees’ honeycombs, the football, Buckminster fuller’s domes and the C60 molecule named after Fuller: buckminsterfullerene. And Thompson was the first to demonstrate it. The second great prophet of morphology is the mathematician and computer pioneer Alan Turing. In 1952 almost nothing concrete was known about the biological mechanism of pattern formation but the problem interested one of the greatest minds of the century. Like D’Arcy Thompson, Turing noticed patterns in living things that could be explained by physical processes. Long before chaos theory, Turing showed mathematically how chemicals diffusing through biological tissue and reacting could become unstable and lead to complex patterns such as the markings on snail shells, leopards, jaguars, giraffes, and Friesian cattle. Many of the patterns in nature can be generated by algorithms, equations that feed back in to themselves. In nature it is not equations that feed upon each other but systems of activation and inhibition. You can see this in a purely chemical reaction – the Belousov-Zhabotinsky reaction – that produces ever changing patterns. Some of these patterns can also be seen in nature, for example in slime moulds. The convergence of mathematics, chemistry and natural forms demonstrates a powerful principle that governs all pattern formation. This convergence also embraces art. Thompson saw parallels between natural processes such as the formation of gourds and technical processes like glass blowing: in each the shape results from an interplay of physical forces. So D’Arcy Thompson regarded beauty as the product of graded curves that shift in a smooth manner from one radius to another. He wrote: “The Florence flask or any other handiwork of the glassblower is always beautiful because its graded contours are, as in its living analogues, a picture of the graded forces by which it was conformed. It is an example of mathematical beauty.” Then there’s Sir Ernst Gombrich, a great art critic who found parallels between natural and human creativity: he wrote beautifully on mimicry and what nature’s copying and stylized warnings mean for the art of human beings: “For the evolution of convincing images was indeed anticipated by nature long before human minds could conceive this trick . . . the art historian and the critic could do worse than ponder these miracles. They will make him pause before he pronounces too glibly on the relativity of standards that make for likeness and recognition.” Gombrich finds various styles of art in nature: a leaf butterfly can fancifully be considered to be “a naturalistic artist,” natural selection having produced a facsimile of the dead-leaf pattern. But the eyespots sported by some butterflies are stylized gestures: “They represent, if you like, the Expressionist style of nature.” The study of beauty in nature and human art is suddenly a live subject again. I have written about parallels between art and nature in The Gecko’s Foot and Dazzled and Deceived. Philip Ball brilliantly brings D’Arcy Thompson up to date in Shapes, one of three volumes spun off from his magisterial survey The Self-Made Tapestry: Pattern Formation in Nature. In 2009 The Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge mounted a seminal exhibition on Darwin and the visual arts, which produced a sumptuous volume: Endless Forms: Natural Science and the Visual Arts. And now in Survival of the Beautiful David Rothenberg surveys the field of nature’s artists, finding parallels between abstract art and the patterns of creatures such as the bower birds and squid. Somewhere to the side of the Saatchi/Turner/Hirst/Emin axis, a new force in visual art is stirring. _ This week’s BBC2 Horizon programme ‘Playing God’, on synthetic biology, had a long item on obtaining spider silk form transgenic goats. We saw a healthy herd of goats at Utah State University’s experimental farm; we saw spider silk being spun. What we weren’t told is that spider silk from transgenic goats was a headline news story almost 10 years ago. Nexia, a Canadian biotech firm, was commercializing spider silk from similar transgenic goats. But the venture failed soon after because the spider silk was way below the quality of natural silk.

Randy Lewis, the researcher at Utah is the world’s expert on synthetic spider silk. He said after Nexia’s failure that he was sure that synthetic spider silk would eventually succeed. So perhaps, 10 years on the tricks have finally been learned? The puzzle is though that earlier this month Randy Lewis published a paper in the US Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences on producing spider silk from transgenic silkworms. The paper commented: “standard recombinant protein production platforms have provided limited progress due to their inability to assemble spider silk proteins into fibers”. That means goats. So, which is it going to be: goats or silkworms? And can spider silk, after decades of study, make the grade? A straw in the wind may be the forthcoming exhibition at the V&A Museum in London of a spectacularly gorgeous cape made laboriously from natural spider silk. It took 4 years and 1.2 million spiders to produce (which is why we need a synthetic process). What might spur researchers on are the remarkable properties of the garment. The cape is a shimmering gold and this is the natural colour of the silk. It also reputedly has a quite special feel, unlike that of normal silk. Perhaps 2012 is going to be the year of spider silk after all this time. _ A dramatic illustration of the fact that in nanotechnology size and shape can sometimes be functional per se comes from recent work on stem cells. Stem cells can be induced to develop into very different cells, simply by growing them on a technical surface with nanoscale pits arranged in different patterns. For example "On a flower shape you get the majority of cells turning to fat, and on a star shape you've got the majority of cells turning into bone."

This is a fascinating new twist on the geometry of nature, a subject pioneered by the great maverick biologist D’Arcy Wentworth Thompson at the beginning of the 20th century. The reason that shaped substrates can have such a dramatic effect relates to the tensegrity structure of cells. Cells maintain their shape through subtle interactions between internal structural elements, the cell membrane, and external forces acting on the cell. The stem cells “read” the patterns on the technical surface and respond in a biological way: a fascinating organic/inorganic interaction. Ref: Nature Materials 10, 559–560 (2011) _ When I began researching The Gecko’s Foot, around a decade ago now, spider silk was the hottest material in the bioinspired armoury. But after the high-profile attempts to produce spider silk from genetically engineered goats failed, the subject was back-burnered. The spider silk genes are so large and repetitive and the processing of the gel in the spinnerets so subtle that the spider kept its secret.

But now scientists at the University of Wyoming have done what might have seemed a good idea form the start: insert the spider silk genes into the silkworm. Silkworms have been commercial silk-producing organisms for millennia so this is promising at last. The research is reported in the US Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. The fact that the silk comes out of Laramie prompts the thought that spider-silk lariats might be a good idea. Rein in that steer with spider power! _ Samphire has recently become a fashionable vegetable and I’ve got to like it as a handy accompaniment to fish. Before its recent elevation it was known by most people for one thing only: the passage in King Lear that goes “Half-way down hangs one that gathers samphire; dreadful trade!” That’s halfway down Dover cliff.

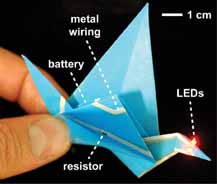

But for me, Samphire means one more thing: it was a poetry magazine of the 1970s and the first magazine of any kind to publish, in 1976, a piece of my writing. Samphire was a typical little poetry magazine of the 1980s. It was edited by Kemble Williams, who was based in Suffolk, and Professor Michael Butler, Professor of German Literature at Birmingham University. Like all little magazines, it had a coterie of writers but the range was wide and I don’t suppose I was the only writer to first-time in its pages. I gradually became a regular contributor and following a few poems I began to review for them. This was invaluable experience – I’m a reviewer to his day and Samphire is where I cut my teeth. It had endearing quirks, such as a rather high proportion of misprints: a review of George Barker that I was rather proud of was when printed seemed to be about one George Baker. Its three times a year arrival on the doormat was a major event – Samphire was a lifeline to a possible alternative world. Of course, back then I romanticised the whole literary business and my small role in it to a ridiculous degree. On holiday one year in East Anglia I called on Kemble Williams at his home, Heronshaw, Holbrook. I remember little of the encounter except that it was good to see the office from which the magic magazine emanated. The magazine folded in 1983 after a 15 year run. The next year I set up shop as a full-time writer. _ Origami is a metaphor for a certain kinds of folding operations which exist in nature and can be replicated in technology. In The Gecko’s Foot I devoted a chapter to the subject. New twists on this are coming to light. George Whitesides has recently been creating paper electronics, electronic circuits printed onto paper. Once the circuits are in place the paper can be folded by traditional origami techniques. So paper aeroplanes can now enter the electronic era, complete with LED lights.

Advanced Functional Materials, 2010, 20, 28-35. Download PDF _ In Dazzled and Deceived, a key theme was the search for effective ships’ camouflage. It began with the eccentric American artist Abbott Thayer at the turn of the 20th century. Thayer had discovered the law of concealing coloration in nature in 1896 (ie animals are dark on top and pale below to counter glare and shadow and make the outline harder to pick out) and became obsessive in his attempts to convince the military to camouflage ships in the same way. He failed and died in despair in 1922

But in my research I discovered that the naturalist Peter Scott, a naval commander in WW2, had introduced a Thayer-like system of camouflage. He’d read Thayer as a boy, camouflaged his own ship in a freelance manner, and then convinced the Admiralty to adopt it as the Western Approaches colour scheme. The documentation was thin and I sought official confirmation in the National Archive and The Imperial War Museum archives. Nothing could be found. Then I found a reference to a naval document – CB3098 – in David Williams’ Naval Camouflage 1914-1945. It seemed that the Admiralty had posthumously acknowledged Thayer after all. I had to get that report. But although the National Archives had the CB series, 3098 was missing. As so often, the net came to the rescue. Bizarrely, it turned out that a Shropshire modellers’ cottage industry sold a facsimile of CB 3098 – The Camouflage of Ships at Sea – to enable modellers to paint their model ships in authentic colours. The report did indeed vindicate Thayer. Given the crushing rejection he had received, the report’s conclusions are astonishing. How Thayer – long dead – would love to have heard these words: “…during the early part of the 1914-1918 war, a number of schemes for reducing the visibility of ships at sea were submitted to the Admiralty. …The soundest of these proposals, whose best points are incorporated in present-day camouflage practice, came from an American artist, Abbott H. Thayer, and from a British biologist, Professor (now Sir John) Graham Kerr; both based their arguments primarily on their observations of the concealing colouration of wild animals and the two sets of proposals were to some extent complementary.” What could have caused this amazing volute face? The report goes on to say that Thayer and Kerr’s argument that “white is the tone for concealment on an evenly overcast grey day – has been thoroughly vindicated in the present war by the Western Approaches, the scheme of camouflage designed by Lt-Cdr. Peter Scott, MOB’S.., R.N.V.R.” The suggestion is that Scott’s inside knowledge of naval operations helped him to carry conviction where the outsiders had failed. The report notes of Thayer and Scott: “it is interesting that the two men who arrived independently of each other, and at an interval of 25 years, at this same unorthodox conclusion should both have brought to the solution of the problem the imagination of an artist and the eye of a practised observer of nature”. Thayer’s odyssey was convoluted in the extreme, as was the research trail in his wake. |

AuthorI'm a writer whose interests include the biological revolution happening now, the relationship between art and science, jazz, and the state of the planet Archives

March 2016

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed