A Nursery web spider (Pisaura mirabilis) has taken up residence in the garden. I’d never seen or known about this spider before. The first thing I noticed, a few months ago, was a very neat cocoon nest in a Spiraea shrub, about 3 inches across and full of spiderlings. The mother, long legged and grey bodied was standing guard. The spiderlings were gone in a few days. In the last few days the female has reappeared with a large yellow egg sac. Today, she’s woven the nest and is standing guard again in more or less the same position as the first brood. Spiderlings awaited. A very nifty spider with an engaging lifestyle. In the picture, the spider is just below the web.

The Invisible Garden at the Hampton Court Flower Show is a great way of opening up the most exciting frontier in the world: the nanoworld. Scientists know this but because the nanoworld can only be seen through microscopes of one kind or another it remains terra incognita for most. Visionaries in the past, long before microscopes, intuited that that the world must be structured in an intricate way at the most infinitesimal of dimensions: Nature, who with like state, and equal pride, Her great works does in height and distance hide, And shuts up her minute bodies all In curious frames, imperceptibly small. Ricardo Leigh (1649-1728), ‘Greatness in Little’ But it is our generation who can finally see what goes on at this level. Nature’s greatest powers – the photosynthesis that powers all life on the planet, the intricate structures that create iridescent butterfly wings; the billions of tiny hairs that allow the gecko to walk on the ceiling –all these are nanophenomena Trying to mimic the powers for our own technical ends is the burgeoning science of bioinspiation. Straightforwardly working with the very small is the even more burgeoning science of nanotechnology. In truth, there is considerable overlap: the gecko sticks by the laws of physics. A dead gecko sticks as well as a live one, which is why there is now a race to create dry gecko-style adhesives. My co-author for our recently published NanoScience: Giants of the Infinitesimal, Tom Grimsey, has worked for some years to make the nanoworld visible via the large-scale kinetic self-assembly tanks he has devised with fellow artist Theo Kaccoufa. The Invisible Garden is the latest show that brings the world of the small into the light of day. Many of nature’s marvels are featured in my The Gecko’s Foot (2006) and the most recent marvels are covered in Nanoscience: Giants of the Infinitesimal (Papadakis, 2014). I have finally got round to reading Steve Jones’ 2007 book Coral. I was attracted to it long ago because I’ve always had a vague hankering to know more about coral reefs (likewise I am always meaning to read Darwin’s pioneering book on the subject but have yet to do so). If I‘d known that the book was about far more than coral I would have dived in long ago.

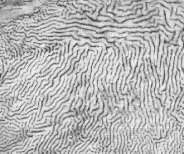

Coral is subtitled A Pessimist in Paradise and Jones is the Prince of Pessimism. The book is in fact a memento mori for the planet and humankind as well as coral: the bleached bones of dead coral serving as the contemplated skull under Jones’s gaze. Steve Jones is a genius who can spin seamless moralities and lugubrious commentaries on human vanity, greed and ugliness whilst all the while informing us of the life of our planet in the clearest terms. Under his gaze, the fornications of Captain Cook’s crew in Tahiti, the absurdities of economic bubbles (coral has been one such, like diamonds and tulips), Eternal Reefs Incorporated of Decatur, who will “arrange for human ashes to be cast into concrete balls and used as the foundations for new coral reefs”, are all as one. Jones is an effortless aphorist, turning what in other hands would be dry facts concerning economics, ecology and ageing into literature: “money is the memory of past bargains”;”Gods, in general, gain immortality through celibacy rather than starvation”. Corals are symbiotic organisms and Jones generalizes his discussion of self-interest and mutualism in nature and human economics until a whole pattern of sex and death and ageing has been woven from the forces of decay – whether of genes or reef-building animals – and the strategies that oppose them. Jones is a master essayist of an almost 17th century kind but his message is wholly of our time, which he believes to be apocalyptically geological rather than merely historical.  The latest Science to land on my desk has a paper on the migration of whooping cranes in America. The cranes are endangered and there is a program to breed them in captivity. An obstacle that had to be overcome was the birds’ annual migration from the breeding site in Wisconsin to Florida. It seems that they rely very heavily on learning from experienced birds so a colony of naive birds facing their first migration has problem. The answer is ingenious and beautiful. A human-powered microlite guides them on their first migration and they are able to find their way back. In subsequent years their navigation improves as the learning process consolidates. In San Diego, earlier this year, I watched pelicans flying home in their shifting V formations. They gave out had aura of control, power and even wisdom. To see that the cranes are able to trust the human navigator for the first trip is very moving. Science, 30 August 2013, pp. 999-1002.  A Brimstone Moth (Opisthograptis luteolata) blew in on the balmy breeze last night. Sorry the poor focus pic doesn't do justice. Must get a moth trap.  The last time I painted my house’s exterior windows I was in hurry and slopped the paint on, especially on the sills. The result was a wrinkled surface where the drying regime in thick layers of paint had pulled the skin into ridges. It had happened before but this time I noticed something in the patterns. I’d seen them before. In 1952, Alan Turing wrote a mathematical paper on pattern formation in biology that was for decades regarded as a curiosity and is now acknowledged as a major contribution to morphogenesis, pattern formation in living systems. Purely mathematically, Turing deduced the patterns that would form in reaction-diffusion systems, ie where a chemical diffusing through a medium, meets another chemical, reacting and continuing to diffuse. The local reaction can change the diffusing pattern at the wave front. Sometimes the product of the reaction can temporarily inhibit the diffusion. The result is complexity, rather as complexity results from iterative equations in fractals. Turing-type patterns exist in nature, in brain corals for instance. My paint wrinkles resemble brain coral very closely. I particular like the bifurcations that appear in these systems. The pomacanthus fish shows this very nicely. Turing has many illustrious achievements to his name. Now I realise he is also the man who made even watching paint dry interesting.  One of the pleasures of nature watching in your own garden is the yearly weather induced variation and the chance arrivals. Once the season is set it’s often dominated by a particular phenomenon. There was the year blackbirds raised a brood in our hedge – the only time in 25 years this has happened. Two winters ago it was a great horde of greenfinches regularly fighting over the bird feeder. Last year many mint moths suddenly appeared on the wild marjoram. This year it has been the gatekeeper butterfly. The hot July gave a boost to butterflies but in North London it seems very few species were left able to take advantage of it. It’s about 5 years since we saw a peacock in the garden. This year, apart the usual early orange tip and a single speckled wood, until July there were a few visits by a comma, a regular in recent years and that was it. There were plenty of whites around in July as predicted but the gatekeepers have been a constant presence, swelling to a maximum of 5 at the same time on the last very hot day of July. Gatekeepers are not urban butterflies and it seems they were never found in London during the years of industrial pollution. They returned to Hampstead Heath in 1991 and seem to be thriving. They’ve certainly been regulars in our garden for the last few years but never on this scale. So good for the gatekeepers but where are the red admirals that used to swarm over a large buddleia bush in the street two doors away? Where are the peacocks?  Since its summer we can be permitted a little idle entomologising. Last summer I was delighted to find for the first time mint moths (Pyrausta aurata) in my garden. These are small, beautifully patterned in various shades of ochre, indigo and brown, day-flying moths. They live on mint or pretty well any labiate flowers. The reason for their appearance was the clumps of marjoram that have thrived in our small North London garden for over 25 years. Two weeks ago a different moth appeared. It had wavy cream patterns on a bluish-black, backround, with yellow on the head and barred on the body. I should have guessed that it’s a relative but only just worked it out when I found two of them this morning. This is the Wavy-barred Sable (Pyrausta nigrata). It is a native of chalk downland so it’s wonderful to find it in North London, blown in from the Chilterns or North Downs. I have always loved the fauna and flora of chalk down land so to find that it is coming to me rather than me having to go to Box Hill is very gratifying. Summer days are here at last. As a recent convert to Geological obsession I have been entranced by Iain Stewart’s BBC2 series Rise of the Continents. So many questions I’d never even asked are answered. Why, for instance, is Antarctica a waste of ice and snow but Australia tropical desert? Until 200 million years ago they were joined as part of the single earth landmass Pangaea, and covered in lush Glossopteris forest. When they sundered, the Antarctic island, surrounded by ocean, began to chill. Wind currents stirred ocean currents to circulate around the continent rather than trade with the warmer waters coming from the tropics. I haven’t worked out yet quite why Australia became tropical desert. Obviously it was always moving north, getting warmer and, drying out, so desertification presumably became unstoppable. Australia, in any case, is still moving and will eventually crash into Asia, unleashing a new mountain range and becoming tropically lush again

Speaking of mountain ranges, I didn’t know that New York sits on the eroded base of a mountain range once of Himalayan dimensions, produced when South America collided with North. A good base on which to build skyscrapers. For those who can access BBC iPlayer, I can’t recommend this series too highly.  There are plants that have survived happily in our garden for nearly 30 years without any attention at all. One of the most notable is cuckoo pint, which at the moment is in flower (much later than usual). I say flower but what you see is the enormous papery cowl and the spike enclosed by it. The flower lies as the base of the cowl and insects attracted by odour and warmth given out by the spike pollinate the plant. The colony has grown steadily in recent years and the plants now attain a great size. This year’s crop is the best ever. |

AuthorI'm a writer whose interests include the biological revolution happening now, the relationship between art and science, jazz, and the state of the planet Archives

March 2016

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed