Butterflies and Babies

World War II was a great stimulus to scientific research. Come peacetime, new techniques were unleashed on the scientific problems that had languished during the war effort. In the October 1952 issue of the Bulletin of the Amateur Entomologists' Society, a small ad appeared that had dramatic but benign medical consequences about 15 years later. It was also profoundly important for the study of mimicry in butterflies. The ad requested eggs, larvae or pupae of swallowtail butterflies, the famously mimetic butterflies first studied by Wallace in the 1860s and it led to a great and productive partnership between Cyril Clarke, a physician and Philip Sheppard, a geneticist.

Together they uncovered the genetic basis of the complex multiple mimetic patterns produced in swallowtails. And this work had a dramatic spin-off in the development of a treatment for a serious disease of new born babies – Rhesus disease. Until the new treatment, babies born with this condition required a blood transfusion soon after birth or they died. The results can be seen in the UK infant mortality figures: in 1950, infant mortality from Rhesus Disease was 1.6 babies per thousand; in 1970 this was still 1.2 per thousand but by the early ’80s it had fallen to 0.1 per thousand.

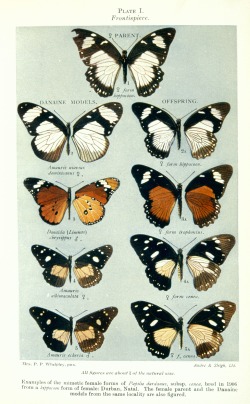

In their butterfly mimicry research, Clarke and Sheppard made thousands of crosses to uncover the genetics of the amazingly creative swallowtails. They discovered that the multiple female forms, which could be produced from a single clutch of eggs, were the work of a single gene that could switch between different forms. But how could such a gene have evolved? Clarke and Sheppard worked before the DNA era and the problem could not be solved until this deep genetic knowledge was available.